On a recent trip to Toronto with my fiancé, we found ourselves with a bit of free time to explore—and for me, that usually means a visit to a cemetery.

Our friends we were staying with suggested we take a walk to Prospect Cemetery, one of the larger and more historic burial grounds in Toronto. It was a chilly, grey day for late April, but despite the dreary weather, it was perfect for a quiet stroll.

There’s something extra special about sharing my love of cemeteries with others. I pointed out some grave symbolism along the way, and our friend—who used to bring their daughter here to bike ride—showed us some of their favourite gravestones.

But I also had a bit of a personal mission too: to visit the grave of J.E.H. MacDonald, one of the founding members of The Group of Seven.

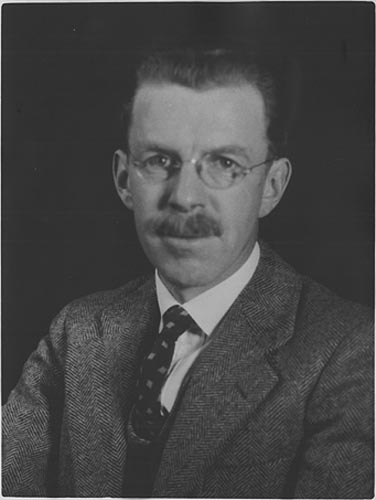

Portrait of J.E.H. MacDonald. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

J.E.H. MacDonald

James Edward Hervey MacDonald was born in Durham, England in 1873 and moved to Canada with his family in 1887.1 He trained in commercial art and landed a job at Grip Ltd., a Toronto design firm that turned out to be a creative hot spot for future Group of Seven artists.2

MacDonald mostly painted with oil, a paint that let him build rich textures and bold, expressive brushwork into his landscapes. He had a special talent for using bright, sometimes unnatural colours to set a mood rather than literal realism. His style focused more toward the feelings and spirit of the landscape rather than detailed realism.2

He was especially inspired by the wild landscapes of Algoma and the Rocky Mountains. His 1916 painting The Tangled Garden shows just how much colour and movement played into his work.2 Besides painting, he also taught art and eventually became the principal of the Ontario College of Art in 1929.2 He helped shape not only Canadian art but also the next generation of artists.

The Tangled Garden, 1916, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario J. E. H. MacDonald, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Controversy

MacDonald made headlines again in late 2023—long after his death—but not for the reasons you’d expect.

The Vancouver Art Gallery had been showing ten oil sketches that were believed to be his work, donated back in 2015. But after some doubts were raised, experts took a closer look—and discovered they were fakes!3

Experts tested the pigments, looked at the brushstrokes, and compared the style to his known works. The materials didn’t match what MacDonald would’ve had during his lifetime, and the way the art was created didn’t quite fit either.4

In a refreshing move, the gallery didn’t just quietly pull the pieces—they created a whole exhibit about the forgery, cleverly called A Tangled Garden.4 The title, a nod to MacDonald’s famous painting, added a bit of irony to the situation.

I respect how the gallery handled it. They used the opportunity to teach people about how art is authenticated and how fakes are detected. In the end, MacDonald’s reputation stayed strong—no copy could ever capture the depth and meaning of his real work.

Prospect Cemetery

J.E.H. MacDonald passed away in 1932 after suffering a stroke. He was only 59. He’s buried in the family plot in Prospect Cemetery in Toronto.5 His grave is simple, tucked away among the rows of headstones. A foot stone with his initials J.E.H.M., and his birth and death dates sits in front of a larger family stone with the MacDonald name. Next to it is another foot stone marked W.H.M. / 1876—1956. I’m not certain, but I believe he might be laid to rest beside his brother, William Henry MacDonald.

There is another foot stone in the MacDonald family plot that is a bit of a mystery. The stone is engraved with the letters J.E.M. and the dates 1920-1926. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to uncover any details about this child’s grave.

Standing in front of MacDonald’s grave felt like another little win in my personal journey to visit the final resting places of all the Group of Seven artists. This was the third grave I’ve visited so far, and I find it fascinating how different each artist’s marker is.

Despite their fame, none of their gravestones are flashy. Like Franklin Carmichael’s grave, MacDonald’s grave didn’t have any grave goods—no paintbrushes, no small stones, no tiny canvases. But there was something powerful about the peacefulness of the spot.

The family plot of J.E.H. MacDonald. Prospect Cemetery, Toronto ON ©2025

There’s something grounding about visiting the grave of someone whose work you admire. You see where their story ended, but you also carry part of their legacy with you. That day in Prospect, under grey skies and the hum of city life just beyond the trees, felt like the perfect moment to reflect on MacDonald’s impact.

Whether through his bright, expressive paintings or the recent conversations around art authenticity, J.E.H. MacDonald still shapes how we see Canada. His grave may be modest, but his influence on Canadian art is anything but.

Thanks for reading!

References:

- J. E. H. MacDonald | The Canadian Encyclopedia

- James Edward Hervey MacDonald | The Group of Seven

- These Group of Seven artist’s sketches are fake — and that’s the point of this Vancouver Art Gallery exhibit | CBC

- Museum Realizes Ten J.E.H. MacDonald Sketches Are Fakes—and Puts Them on Display | Smithsonian Magazine

- J E H MacDonald | Mount Pleasant Group