I first learned about René M. Caisse by chance during a visit to downtown Bracebridge, Ontario. The restaurant I had planned to visit with my Mom was closed, as was most of the downtown core, because it was Easter Monday. Only one place was open, and it just so happened to be across the street from a statue of René M. Caisse.

After reading the plaque, I pulled out my phone and did a quick search to discover that she was the woman behind the herbal remedy known as ESSIAC.

I had never heard of Caisse before, or ESSIAC, for that matter. The more I read, the more I had to know.

What exactly was ESSIAC, and how did this small-town nurse end up known around the world? A little more searching revealed that her final resting place was also in Bracebridge, so I added a stop to our trip to pay our respects. By the end of the day, I would find myself standing beside her gravestone, reflecting on how one small discovery downtown had turned into a much larger story.

René M. Caisse

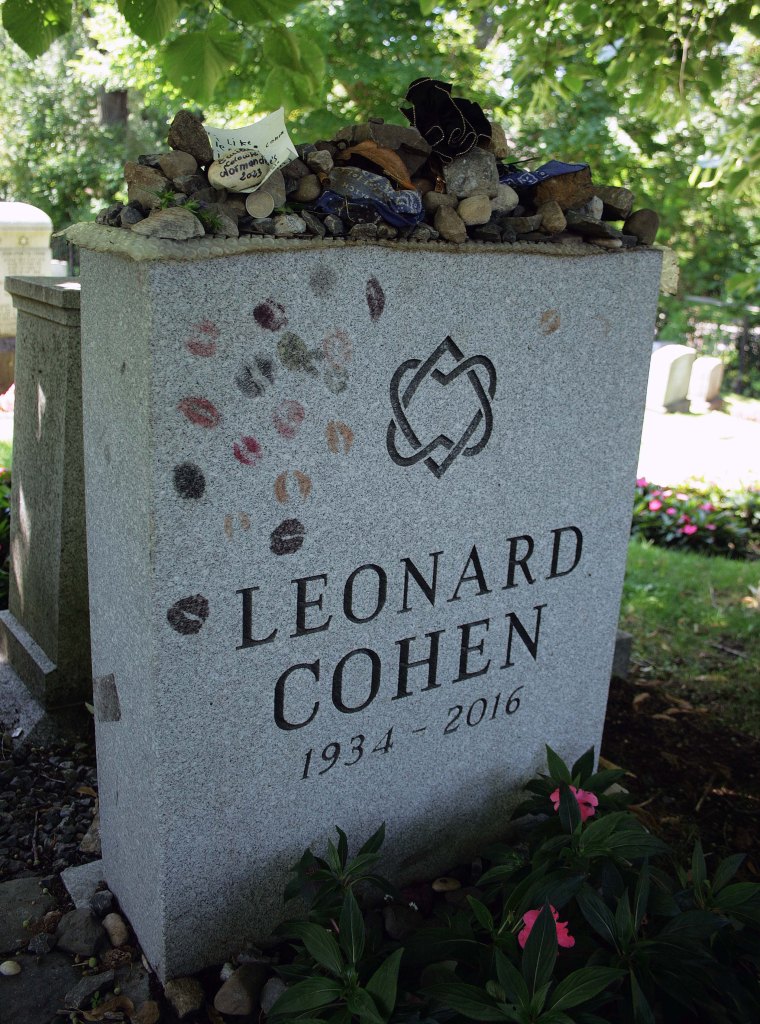

René M. Caisse was born on August 11, 1888, in Bracebridge.1 Trained as a nurse, she developed an herbal formula for patients that she later named “ESSIAC”, her last name spelled backwards.2 The formula included roots, bark, and leaves of plants such as burdock root, sheep sorrel, slippery elm, and rhubarb root.3

In her manuscript, I Was “Canada’s Cancer Nurse”: The Story of ESSIAC, Caisse described how she first learned about the herbs that would later shape her life’s work. In the mid-1920s, while serving as head nurse at the Sisters of Providence Hospital in northern Ontario, she encountered an elderly patient who had once been diagnosed with advanced cancer.4 According to Caisse, the woman told her that decades earlier, a local Indigenous medicine man had offered her an herbal remedy. The woman chose to follow his instructions, preparing a daily tea from the specific plants he identified in the region. When Caisse met her nearly thirty years later, she seemed to be in remission.4

Caisse wrote that at the time, a cancer diagnosis often felt like a death sentence.4 The patient’s story stayed with her. She recorded the names of the herbs and later began refining the formula, eventually combining several plants into what would become known as ESSIAC.4

Caisse maintained that she never claimed to have discovered a guaranteed cure for cancer, explaining that her goal was to control the disease and pain relief.4

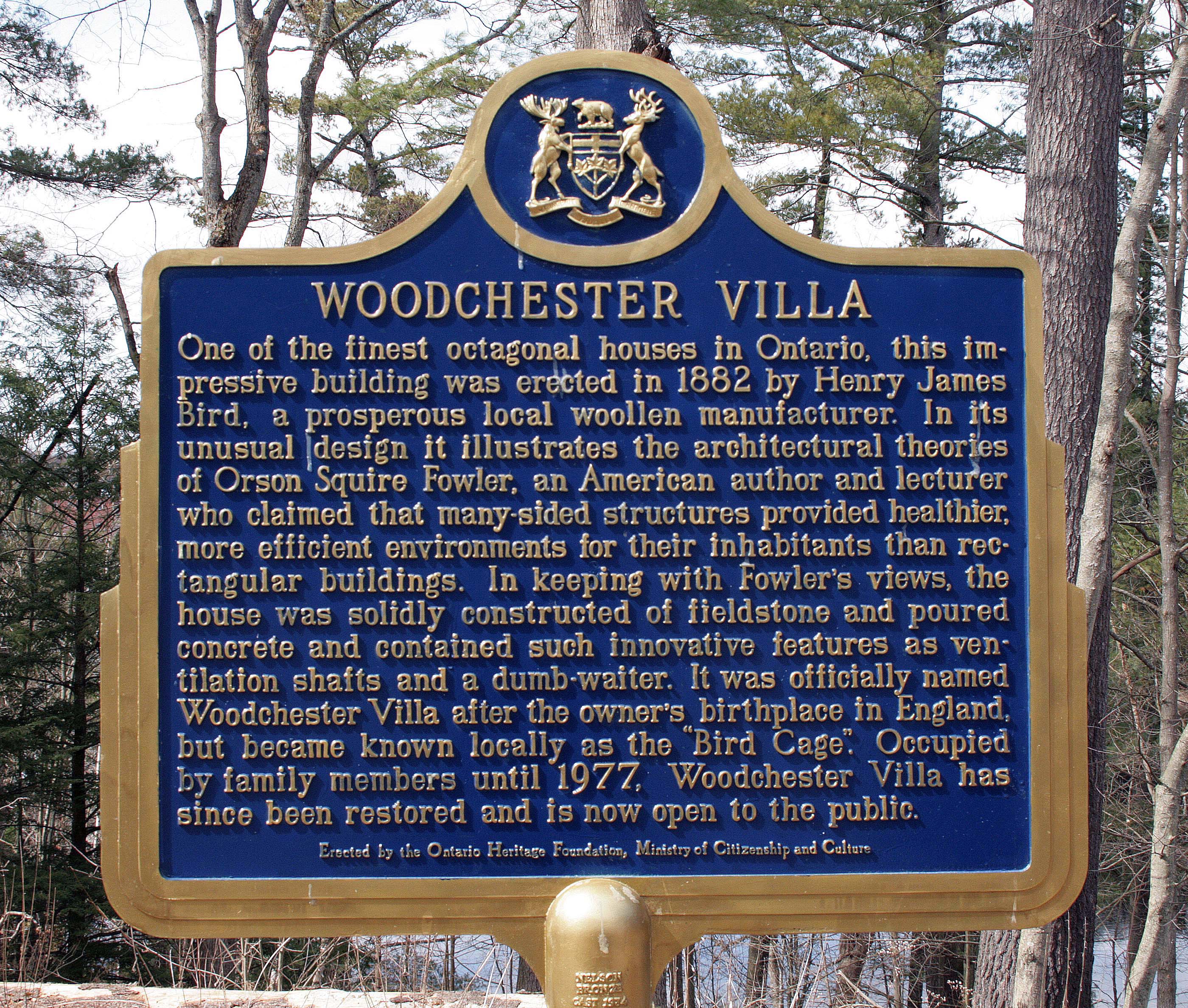

A bronze statue in the Bracebridge downtown core honours her work. The sculpture, created by Huntsville artist Brenda Wainman-Goulet, stands on a stone base near where her clinic once operated.5 During the 1930s and early 1940s, thousands of patients travelled to the Muskoka region hoping to visit her clinic.2

Statue of Rene M. Caisse. Bracebridge ON ©2025

But, along with the attention came controversy.

The medical establishment questioned the effectiveness of her remedy, and government reviews in Canada concluded there was no clinical evidence to support ESSIAC as a treatment for cancer.5 Some studies even indicated it could cause possible harm.3 Caisse, for her part, believed powerful interests stood in the way of broader acceptance. She wrote that it would make established research foundations “look pretty silly if an obscure Canadian nurse discovered an effective treatment for cancer.”4

Even so, people still seek out ESSIAC, drawn by word of mouth and the hope that this herbal blend might offer relief when other options feel limited. Her legacy remains visible in Bracebridge and beyond, through her statue, a theatre named in her honour, and through the many stories of those who came to her clinic in search of help.5

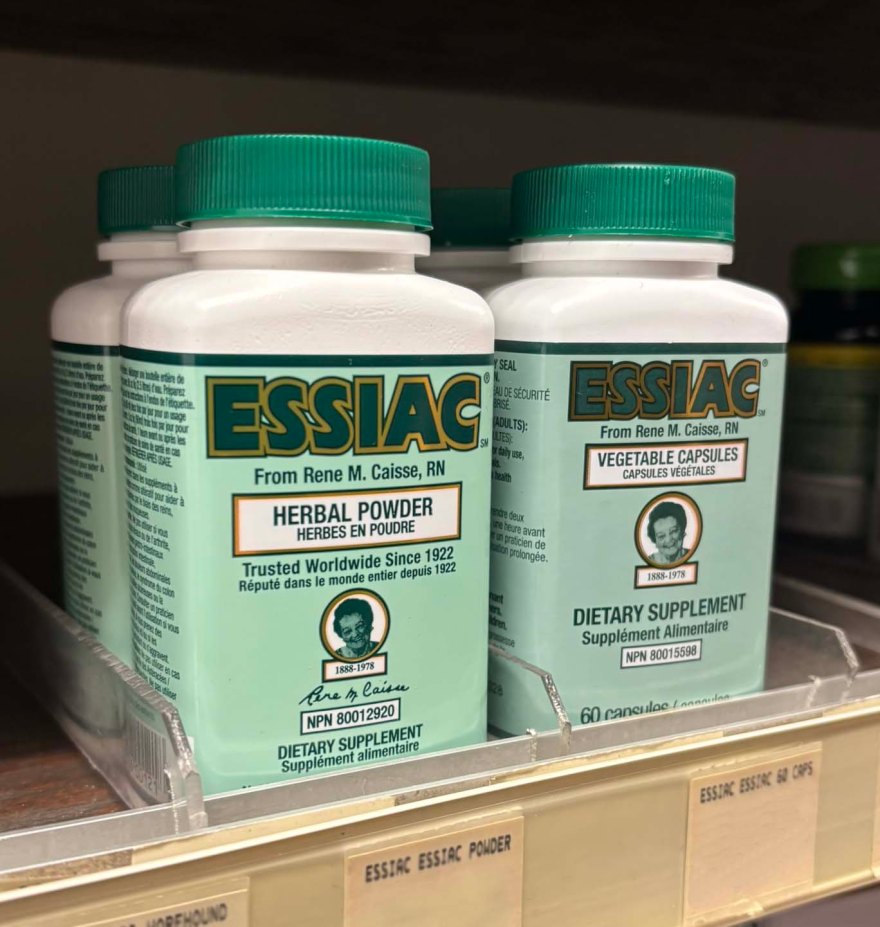

Beyond Caisse’s time, the remedy has been commercialized and repackaged. For example, the company ESSIAC®, through ESSIAC Canada International, touts its herbal blend as “trusted since 1922,” with marketing of powdered, capsule, and liquid extract forms.6 Meanwhile, Resperin Canada Limited claims to prepare “Resperin’s Original Caisse Formula Tea” using Caisse’s original herbal recipe.7

Even with all the marketing around it today, independent sources still say there’s no reliable evidence that ESSIAC works as a cancer treatment.3

The main ingredients of ESSAIC; burdock root, sheep sorrel, rhubarb root, and slippery elm.

Months after our trip to Bracebridge, the story followed me home. I was pleasantly surprised to discover that my local natural food store carries a version of ESSIAC. Standing in the aisle and seeing her name and likeness on a bottle nearly a century later made the story feel less like history and more like something still unfolding.

Curious, I asked what forms they carried and ended up purchasing a small sample of the four main herbs that make up ESSIAC. The store sells it as loose herbs, herbal powder, in capsule form, and as a pre-mixed blend packaged in a large bag. The clerk told me ESSIAC is popular and they always keep it in stock. She mentioned that sales tend to come in waves, and that often people who have just received a cancer diagnosis come in looking for it.

It’s interesting to see how Caisse’s legacy still lives on the shelves of health shops nearly a century later, with people continuing to turn to it in moments of uncertainty. Whatever conclusions science has reached, the hope attached to her name has clearly endured.

Bottles of ESSIAC on the shelf of my local health food store.

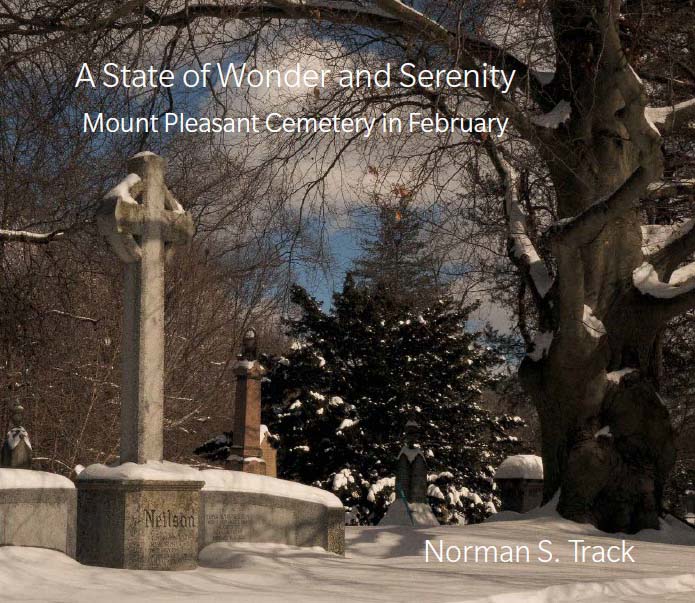

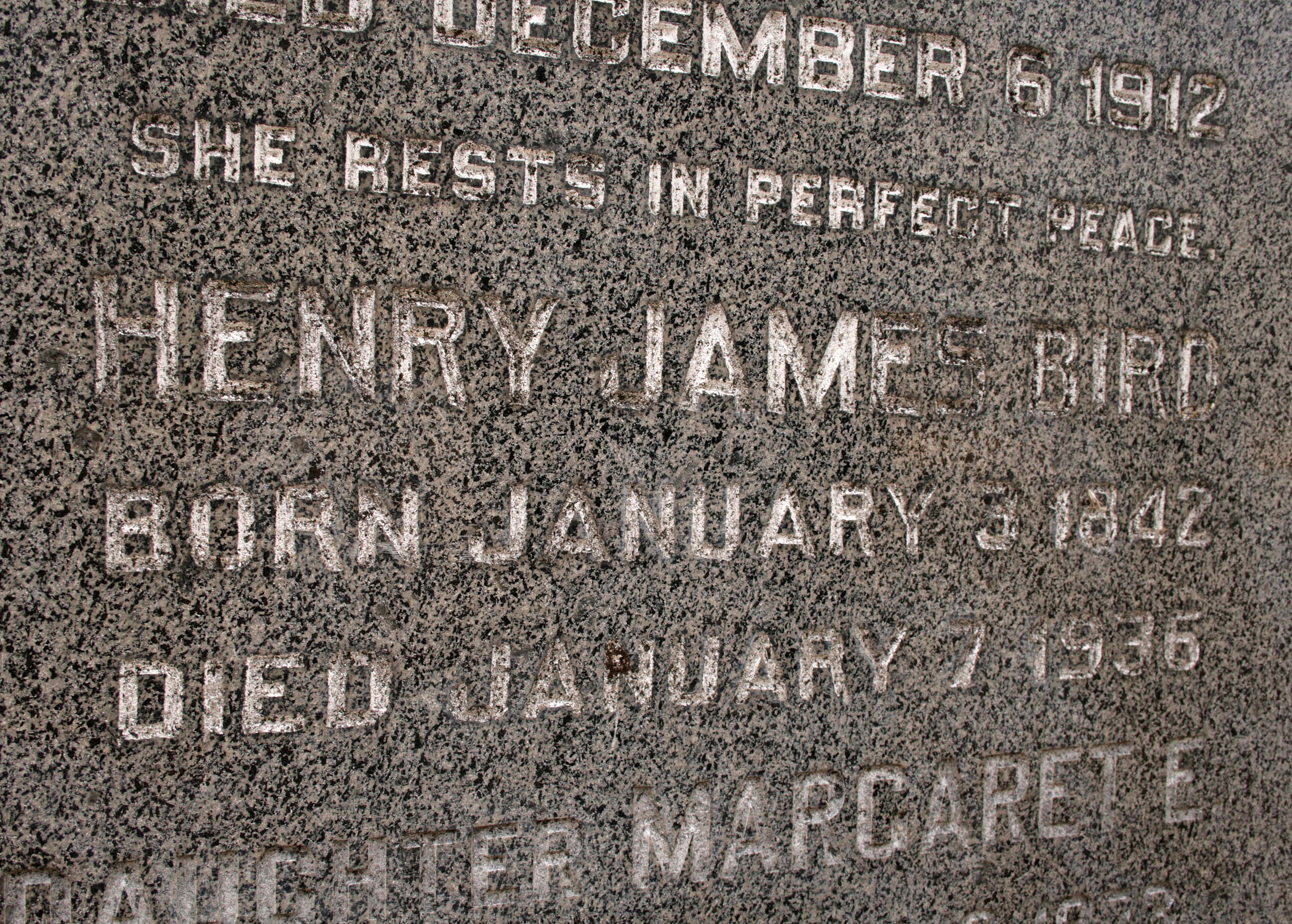

René M. Caisse McGaughey suffered a broken leg after a fall at her home, from which she never recovered.8 Five weeks later, on December 26, 1978, she passed away at the age of 90.8 Although she received tempting offers to establish clinics in the United States, she chose to remain in Canada. In her writings, she explained that her ancestors had come to Canada from France in the 1700s and that she was determined to prove the merit of ESSIAC in Canada so the country would receive the credit.4 Not far from the statue that first caught my eye, Caisse now rests in Saint Joseph’s Roman Catholic Cemetery in Bracebridge.

Finding her grave felt like the final piece of the story. From spotting the statue downtown, to learning about her work, to standing at her grave, the story had come full circle. Her gravestone, which acknowledges her as the “Discoverer of ESSIAC” is simple yet powerful.

Walking among the rows of gravestones, I reflected on how her story is deeply rooted in this place. She is remembered not only because she lived and worked in Bracebridge, but because the community continues to honour her in visible and lasting ways.

In many ways, this visit brought together local history, public memory, and my own curiosity, all meeting at her final resting place.

Saint Joseph’s Roman Catholic Cemetery, Bracebridge ON ©2025

René Caisse’s life offers a fascinating mix of determination, controversy, and local remembrance. She stands out as a woman from a small town who believed in an herbal remedy, faced bureaucracy, and left a legacy that is still visible today.

While the scientific verdict on ESSIAC is still debated, the story of its creator remains part of Canadian medical history.3

Visiting her statue in downtown Bracebridge, noticing her name on a product shelf, and standing beside her grave reminded me that remembrance takes many forms. Sometimes it’s cast in bronze, sometimes printed on packaging, and sometimes it’s etched in stone, just waiting for someone to notice.

Thanks for reading!

References:

- Timeline of Essiac History | Rene Caisse Revolutionary Nurse & Holistic Pioneer

- Who was Rene Caisse? | ESSIAC Info

- Questionable Cancer Therapies | Quackwatch

- I Was “Canada’s Cancer Nurse”: The Story of ESSIAC by René M. Caisse, R.N. | Manuscript

- Honoured in Bracebridge | ESSIAC Info

- ESSIAC Rene Caisse | ESSIAC Canada International

- The 4 Herbs in René Caisse’s Formula | Resperin Canada Limited

- René M. Caisse McGaughey | Find a Grave