Some cemeteries feel alive with history, and sometimes with something else entirely!

Drummond Hill Cemetery in Niagara Falls is one of those places. Known as the site of one of the fiercest battles of the War of 1812, it’s also considered Canada’s most haunted cemetery.

Long before its haunted reputation took hold, Drummond Hill was a popular tourist stop, even rivalling Niagara Falls. Visitors came for battlefield tours led by veterans eager to share their stories.1

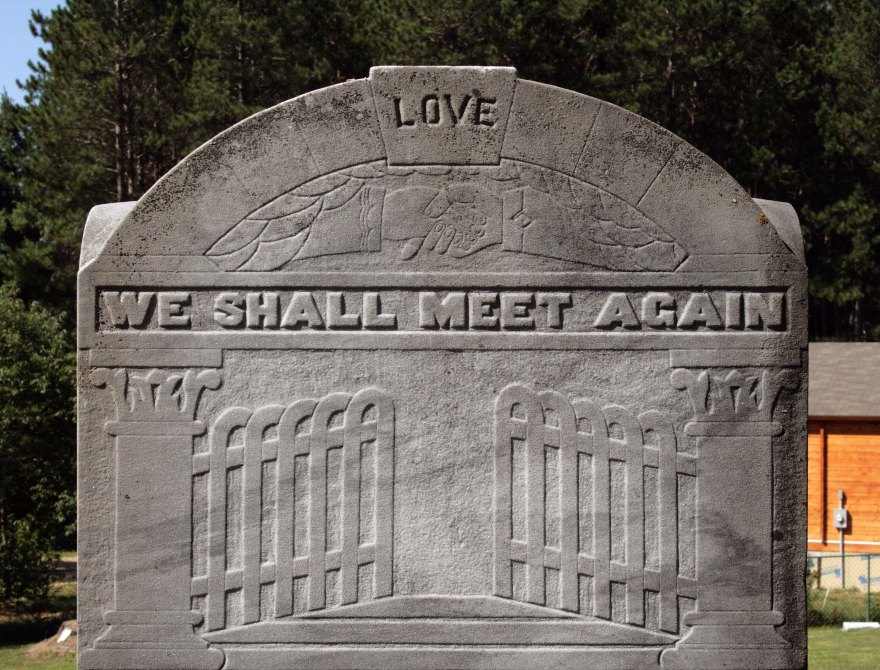

Cemetery gates. Drummond Hill Cemetery, Niagara Falls ON ©2024

Drummond Hill Cemetery

Drummond Hill was once farmland, but on July 25, 1814, it became the site of the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, one of the bloodiest conflicts of the War of 1812.2 The hill’s high ground made it strategically important, and the fighting went on for six hours before darkness and heavy losses brought it to an end.2 Both sides lost more than 800 men, and although each claimed victory, the Americans withdrew the next day, ending their advance into Upper Canada.2

Today, a large stone monument stands on the hill to honour those who fought and to mark the battlefield.3 Beneath it lies a vault containing the remains of 22 British soldiers.3

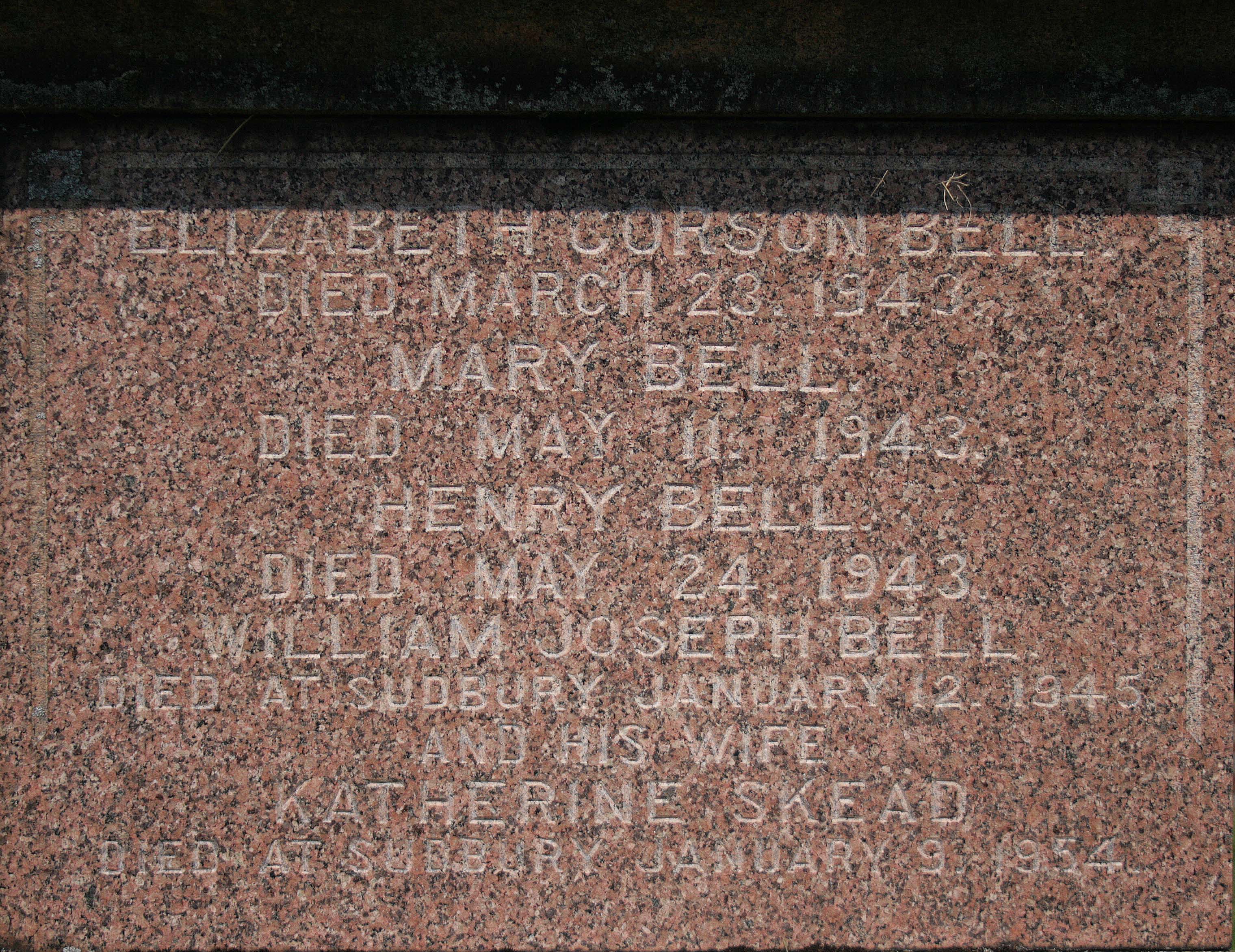

The first recorded burial at Drummond Hill is John Burch. He was originally buried on his farm in 1797 and re-interred here in 1799.3 That means this ground was already being used as a burial place well before the battle. Over time, the cemetery grew to roughly 4 acres and now contains more than 25,000 burials.4 The site is managed by the City of Niagara Falls and remains semi-active, though plots are no longer for sale.3

Among those buried here are veterans, Loyalist settlers, and many early Niagara families. One of the most visited graves belongs to Laura Secord, the woman who warned British forces of an American attack during the War of 1812.4 Another notable grave is that of Karel Soucek, the daredevil who famously survived his barrel plunge over Niagara Falls.5 You will also find markers and monuments for soldiers and local leaders from the region’s early days.3

Drummond Hill Cemetery, Niagara Falls ON ©2024

Haunted

With its violent past and long history, it’s no surprise Drummond Hill has a haunted reputation. Many stories connect back to the battle, where soldiers were killed and buried on the grounds.6 Visitors and locals have reported seeing ghostly soldiers walking among the gravestones, or appearing at a distance before fading away.6

It’s said that the cemetery is haunted by two distinct groups of soldiers.1 One group is a troop of five soldiers dressed in Royal Scots uniforms, limping across the former battlefield before vanishing.1 The second group is said to consist of three British Soldiers in red coats, slowly making their way up the hill and settling into a steady march, before disappearing.1

Laura Secord’s monument, which features a lifelike bust, has also been linked to supernatural occurrences. Some visitors say that her statue seems to watch them as they walk by, as if she’s still keeping a watchful eye on things.1 These reports, combined with the age of the cemetery and its battlefield history, make Drummond Hill a place where history and the supernatural feel closely connected.1

Drummond Hill Cemetery, Niagara Falls ON ©2024

When I visited Drummond Hill, I made sure to stop at Laura Secord’s grave. Standing in front of her stone was moving, knowing her bravery has become such a lasting part of Canadian history.

During my visit, I did have one unsettling experience, but it had nothing to do with the supernatural.

I came across someone under the influence, wandering through the cemetery. For the first time in all my cemetery visits, I felt unsafe. It was a harsh reminder of how deeply the opioid crisis has reached into our communities, even historic sites like this. That moment pulled me out of the past and reminded me of the struggles happening right now.

Drummond Hill Cemetery is layered with stories. It carries the weight of the War of 1812, the lives of pioneers and heroes, and the ghostly legends of soldiers who never left. It’s a place where history and mystery meet, and where the past feels close. Visiting left me reflecting not only on the history that shaped this ground, but also on the realities of the present.

Haunted or not, Drummond Hill remains one of Canada’s most fascinating and important cemeteries.

Thanks for reading!

References:

- Haunted Cemeteries: True Tales From Beyond the Grave by Edrick Thay | Book

- Battle of Lundy’s Lane National Historic Site of Canada | Government of Canada

- Drummond Hill Cemetery | City of Niagara Falls

- Drummond Hill Cemetery | Find a Grave

- Karel Soucek | Find a Grave

- The Most Haunted Cemetery in Canada is Drummond Hill | Ghost Walks