I rarely stop to think about where our drinking water comes from, let alone whether it’s safe.

In May 2000, the small town of Walkerton, Ontario, faced one of Canada’s worst public health disasters. Contaminated water led to the deaths of seven people and made more than 2,300 people sick.1

Walkerton is about a four-hour drive from where I live, and this year marks the 25th anniversary of that tragedy. In June, my mother and I took a road trip there to visit some of the sites connected to the outbreak and to pay our respects to the lives that were lost.

Walkerton water tower, Walkerton ON ©2025

What Happened in Walkerton

You might remember hearing about this on the news. Walkerton’s drinking water became contaminated with E.coli.1 The source of the contamination was traced back to Well #5, where runoff from a nearby farm had entered the groundwater. Heavy rainfall in early May 2000 carried manure into the well, and the danger was made worse by human error and poor safety practices at the time.1

For days, residents kept drinking the water, completely unaware of the risk. Once it was realized what was happening, it was too late. Within weeks, seven people had died and more than 2,300 others became seriously ill.1 Many survivors continue to live with lasting health problems even today.

The Walkerton Inquiry, led by the Honourable Dennis R. O’Connor, later showed that this wasn’t just one bad well—but a series of failures. Training was inadequate, oversight was weak, and protocols weren’t followed the way they should have been. Out of this tragedy came stricter water safety regulations for Ontario, which eventually shaped how drinking water is managed across Canada.2

Visiting Walkerton

When we arrived in Walkerton, our first stop was the Walkerton Clean Water Centre. It first opened in 2004, and since then has trained over 23,000 water system operators.3 The new state-of-the-art building, which we visited, was opened in 2010. It features a demonstration water distribution system for hands-on training, more room to host seminars, and space to conduct research.3

In May of this year, they offered tours of the facility, close to the anniversary of the tragedy. The timing didn’t work out for us to take a tour, but I still wanted to take a look at the building.

It’s a modern building, with a lovely koi pond just outside its main doors. The large windows have a nice view of the pond, and let in a lot of natural light. There is also a small pond across from the entrance, overgrown with tall grass and cattails, that is surrounded by a little trail loop. I imagine the staff take advantage of that little walking trail on their lunch breaks. I think the water features, while also being pretty, act as little reminders of how important water is to our ecosystem and us.

Walkerton Clean Water Centre, Walkerton ON ©2025

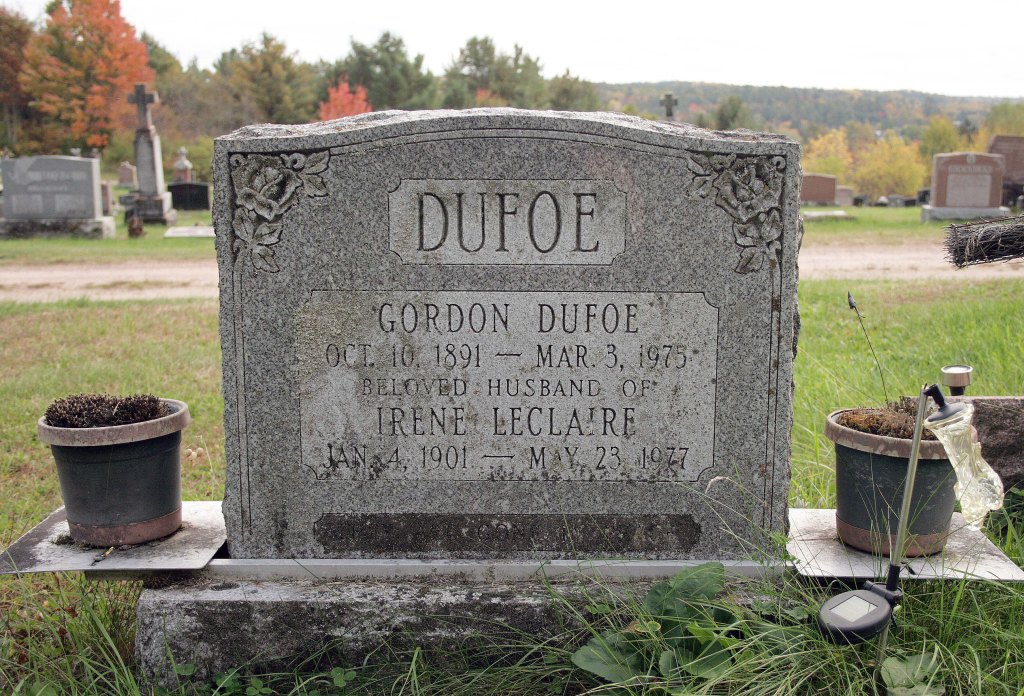

Our next stop brought us to a small cemetery that wasn’t connected to the tragedy. I am not one to pass up a cemetery visit though, so we made our way to visit. It just so happened to be very close to the Walkerton water tower. After that, we decided to visit a few more cemeteries, the last one of the day being Calvary Cemetery.

Calvary Cemetery is on the outskirts, just south of the town. This cemetery visit was important for our journey, as it is the final resting place of two people who died in the water tragedy.

Edith Pearson, a mother of five and a grandmother of 13, passed away at the age of 82.4 Not far from her rests Lenore Al, a retired part-time librarian, who passed away at the London Health Sciences Centre at the age of 66.4 Their memorial services were held both during the same week.5

It was a very reflective visit, as my mother and I walked the rows searching for these specific graves. It was a scary thought to think what could happen by just drinking a glass of water. Standing in front of their graves also made their story real, bringing it off the page and into reality.

Calvary Cemetery, Walkerton ON ©2025

After that somber visit, I thought it might be a good idea to visit something a little more hopeful. The Walkerton Heritage Water Garden features a waterfall that gushes out from a crack in a large rock formation. It’s inspired by the biblical story of Moses, who struck a rock in the desert to bring water to the Israelites.6 It represents water as a positive symbol of life, healing and renewal. The waterfall pours into a small pond that is surrounded by a larger walking trail. There are benches and small clusters of flowers and tall grass that dot the path that leads you back to the memorial fountain.

It was a hot day when we visited, so the occasional cool spray from the waterfall was very welcome. It was a nice little spot for a small walk, but the constant running water made it hard to forget why it was there.

Walkerton Heritage Water Garden, Walkerton ON ©2025

Our first day in Walkerton was a long one. Shortly after our walk, we found something to eat and then settled in to our motel for the night. We had one more site we had to visit.

The next morning, after a good breakfast, I wanted to find Well #5.

Sometimes while planning and researching, it can be tricky to find exact locations, even in this digital age. But I thought we have to give it a try. So with only a street name in my GPS we headed out.

Slowly driving down the dirt road, we kept our eyes peeled for signs of the well. I was getting worried as we reached the end of the road, but I caught the glimmer of what looked like a silver plaque.

We found the well, which has since been capped off, tucked in behind a small building on the edge of a farmer’s field. Today, it’s just a large cement pad with a small silver plaque. If you didn’t know what you were looking at, you may think nothing of it, but the plaque tells the whole story.

“Well 5 Memorial / This plaque marks the location of Walkerton’s former Well 5 / which supplied a portion of the town’s drinking water from / 1978 into the spring of 2000. In mid May of the year 2000, / extremely heavy rains washed a toxic blend of biological / pathogens through the soils and into the vulnerable shaft of / Well 5 and ultimately into Walkerton’s Municipal drinking / water system. The resulting contamination of the town’s / drinking water system lead to the deaths of seven people and / caused thousands of others to fall ill. It is hoped that all those / who visit this location will reflect upon the multiple causes of / this tragedy and will be filled with a renewed reverence for the / comprehensive stewardship of the waters that sustain us all.”

Finding the well was a moving moment, and as the plaque suggested, my mother and I took some time to reflect as we looked into the farmer’s field and at the old well.

Well 5 Memorial, Walkerton ON ©2025

Lasting Impact

The story of Walkerton didn’t end in 2000. For many survivors, the contamination left behind long-term health complications that they will carry for the rest of their lives. One of those people was Robbie Schnurr, who became seriously ill during the outbreak.7 The illness damaged his kidneys and digestive system, leaving him to cope with constant pain and health struggles for nearly two decades.7

In May of 2018, Robbie made the heartbreaking decision to end his life through Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID).7 He was just 51 years old. The illness caused by Walkerton’s poisoned water was just too heavy a toll.7 Robbie’s story is a reminder that the impact of what happened in Walkerton wasn’t confined to the weeks of the outbreak. It rippled out for years, forever altering lives and families.

Moving Forward

One of the outcomes of the Walkerton Inquiry was a complete overhaul of Ontario’s drinking water regulations. New laws were brought in to ensure public accountability, proper testing, and better training for those operating municipal water systems—all with the goal of making sure something like this never happens again.2

And yet, even in 2025, not every community in Canada can count on that promise. Some First Nation reserves continue to struggle with unsafe drinking water, some living under boil-water advisories that have lasted for years.8

It’s a frustrating and heartbreaking reality. Safe drinking water should be a basic human right, not a privilege.

Visiting Walkerton was an educational and somber experience. Standing at the memorial fountain, walking through the cemetery, and pausing at Well #5 all carried more weight than just stops on a road trip. It was a chance to reflect on a tragedy that forever shaped this small town, and to see how its lessons continue to make Ontario’s communities safer today.

Twenty-five years later, the Walkerton water tragedy remains a powerful reminder of what’s at stake when safety is ignored. It also reminds us of the resilience of a community that continues to honour those lost, while moving forward with a commitment to never forget.

Thanks for reading!

References:

- Inside Walkerton: Canada’s worst-ever E. coli contamination | CBC

- Commemorating Walkerton – 20 Years Later | Drinking Water Source Protection Quinte Region

- New Walkerton Clean Water Centre Opens | Ontario.ca

- The Walkerton Tragedy | Globe and Mail

- Second funeral held in town with tainted water | CBC

- Walkerton Heritage Water Garden | Bruce Grey Simcoe

- In 2000, Walkerton’s poisoned water ruined his life. He decided it was time to end it | Toronto Star

- 30 years under longest boil-water advisory in Canada, Neskantaga First Nation pushes for new treatment plant | CBC