Cemeteries are places of reflection, history, and, for some, a source of artistic inspiration. After nearly two decades of photographing cemeteries, I often find myself thinking about how to balance documenting these spaces with respecting the people who rest there.

Is it ever inappropriate to photograph a grave? Are there certain cemeteries or gravestones that should be off-limits? These are questions that I, and I’m sure many other cemetery photographers, often think about.

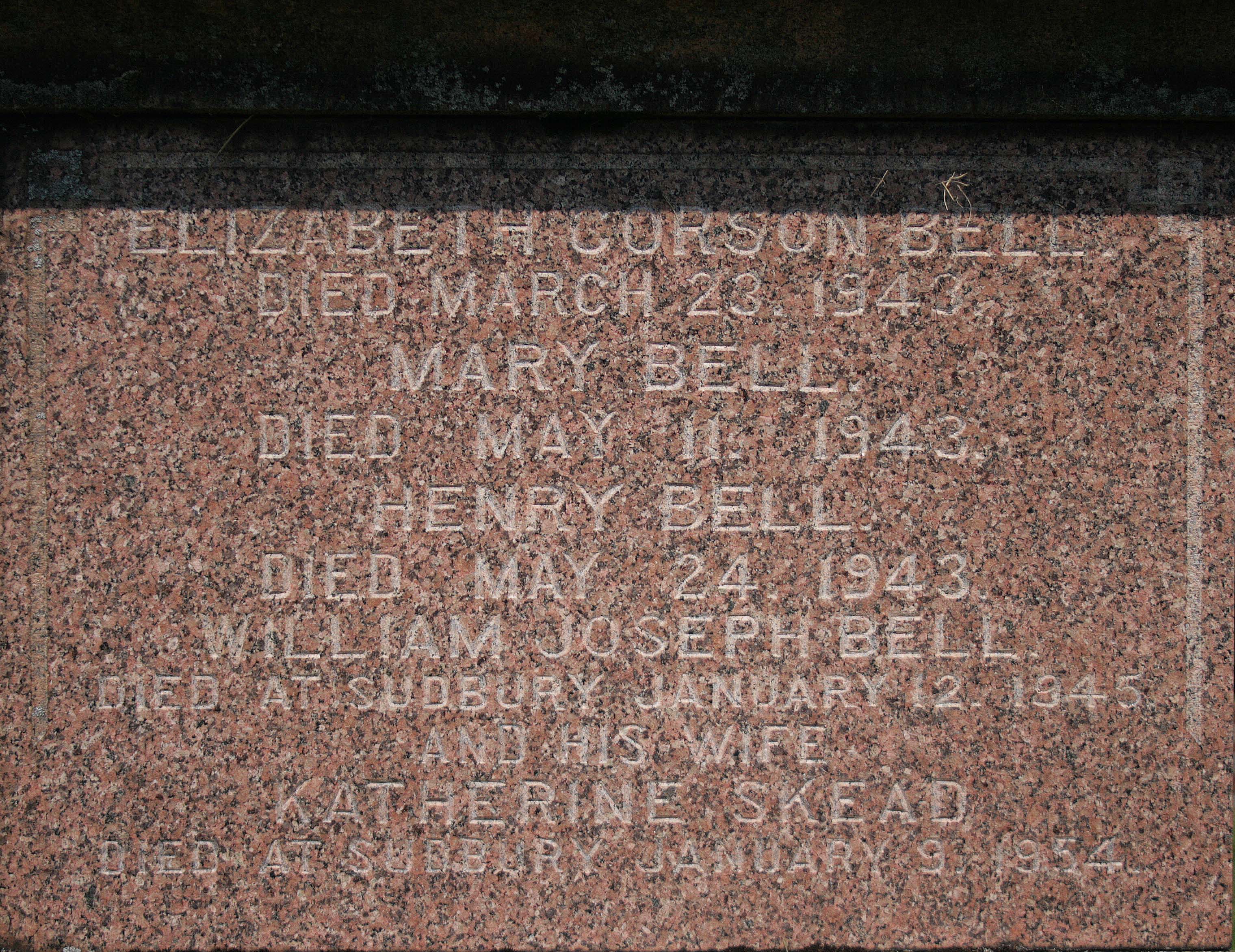

Cemeteries are undeniably beautiful. From intricate gravestones and elaborate monuments to the way nature blends with history, they offer countless opportunities to tell stories through photography. Many photographers, myself included, see this work as a form of preservation. Stone doesn’t last forever, and time can slowly erase names, symbols, and details. Sometimes, a photograph becomes the only lasting record of a gravestone.

But while photography can help preserve history, it’s just as important to remember that cemeteries are sacred places. What feels like a meaningful or artistic image to one person could feel intrusive or disrespectful to someone else.

Elora Cemetery, Elora ON ©2025

Are Cemeteries in Ontario Public or Private Spaces?

The first step in thinking about the ethics of cemetery photography is understanding whether a cemetery is public or private. In Ontario, cemeteries are regulated by the Bereavement Authority of Ontario (BAO), which oversees the rules and standards that govern their operation. Many cemeteries, especially older ones, are municipally owned and open to the public. Even so, public access does not always mean unrestricted access. Some cemeteries do have specific rules around photography, so it’s always a good idea to check for posted signage or guidelines before starting to take photos.

Private cemeteries, which are often operated by religious groups or independent organizations, can enforce stricter rules. Some may require permission, particularly if photos will be used commercially. A few years ago, a proposed bylaw in Waterloo, Ontario, suggested restrictions on cemetery photography in city cemeteries. This sparked a debate among genealogists and historians who rely on photos for research and preservation.1

It’s also important to recognize that cemeteries carry cultural, religious, and spiritual meaning for many people. Over time, I have learned that different cultures have their own unique traditions around death and burial, and those traditions should always be respected. In some cases, photographing certain graves or monuments may be discouraged, or photography itself may be seen as inappropriate. I try to be mindful of these differences when I am visiting and photographing cemeteries, and when I am unsure, I see it as a cue to slow down or ask questions. Being aware of these differences and asking for permission when needed, goes a long way toward practising photography that feels respectful rather than intrusive.

I don’t always get it right, but I try to approach each visit with respect and a willingness to learn. For me, that respect often extends beyond my own photography and into finding ways to help others connect with these places of rest.

Photographing cemeteries isn’t just about capturing beautiful or historic images. It can also be a meaningful way to help others. I’ve been a member of Find a Grave for over 11 years, where photographers volunteer to take photos of gravestones for people who request it. For those who can’t visit a cemetery themselves, these photos can be incredibly important.

If you’ve never considered volunteering as a cemetery photographer, it can be a rewarding way to give back while helping preserve family histories. Find a Grave is a great place to start!

The gratitude I’ve received from people who’ve found photos of their ancestor’s graves through the site has been deeply meaningful. Volunteering in this way can also create a sense of community by helping others access information and preserve legacies they might not otherwise have been able to reach.

Elora Cemetery, Elora ON ©2025

Cemetery photography is a deeply personal practice. For some, it’s all about exploring history. For others, it’s about artistic expression. The most important thing is approaching it with care and awareness. If you’re ever unsure whether a photo is appropriate, it helps to pause and imagine how you would feel if it were your loved one’s grave.

I believe in the principle of “taking nothing but pictures, leaving nothing but footprints.” For me, I think ethical cemetery photography comes down to intentions. Are you there to honour, preserve, and respect? If so, I think your work will reflect that naturally.

What do you think? Where do you draw the line between art and respect when it comes to cemetery photography?

Thanks for reading!

References: