There’s something about the start of a new year that makes me want to jump right in, and what better way to do that than with a stone story.

This one had been on my must-see list for a while, and last summer I finally got to see it in person on a road trip with friends. Tucked away in Aurora Cemetery in Aurora, Ontario, is one of the most unique gravestones I’ve ever come across: a miniature version of the Empire State Building.

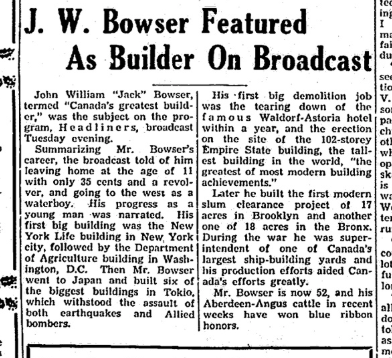

John William “Jack” Bowser was born in 1892 in Aurora, Ontario, and went on to become a successful businessman and entrepreneur.1 After moving to New York City, Bowser made his fortune in construction, eventually becoming closely associated with one of the most famous buildings in the world, The Empire State Building.2 Dubbed “Canada’s Greatest Builder,”2 Bowser was deeply involved in the project and served as the construction superintendent, which helps explain why this iconic skyscraper would later appear in such an unexpected place.3

Despite his success in the United States, Bowser maintained strong ties to his hometown. He returned to Canada, and remained active in construction. Bowser owned and operated ABC, Aurora Building Corp. until his death, in 1956.1

The Aurora Era, Serving Aurora and District. Aurora, Ontario, Thursday, December 20th, 1945

A Skyscraper Among the Stones

Bowser’s gravestone is impossible to miss. Carved in the unmistakable shape of the Empire State Building, the monument rises above the surrounding stones, complete with stepped setbacks that mirror the Art Deco design of the real skyscraper.4 Standing roughly 10 feet tall, the stone serves as a tribute not only to Bowser himself, but also to his pride in being part of a project that briefly held the title of the tallest building in the world.5

It’s also a fascinating example of how personal identity and legacy can be captured in stone. Rather than traditional symbols or lengthy inscriptions, this monument tells Bowser’s story at a glance. Even if you didn’t know his name, the shape of the stone immediately sparks curiosity and invites questions.

Aurora Cemetery

Aurora Cemetery is the final resting place for many notable local figures, but Bowser’s grave is by far one of its most talked-about features. The cemetery itself is well-maintained and easy to walk, making it a worthwhile stop even beyond this one monument. That said, it’s easy to see why this gravestone has become something of a local landmark and a favourite stop for cemetery enthusiasts and curious visitors alike.

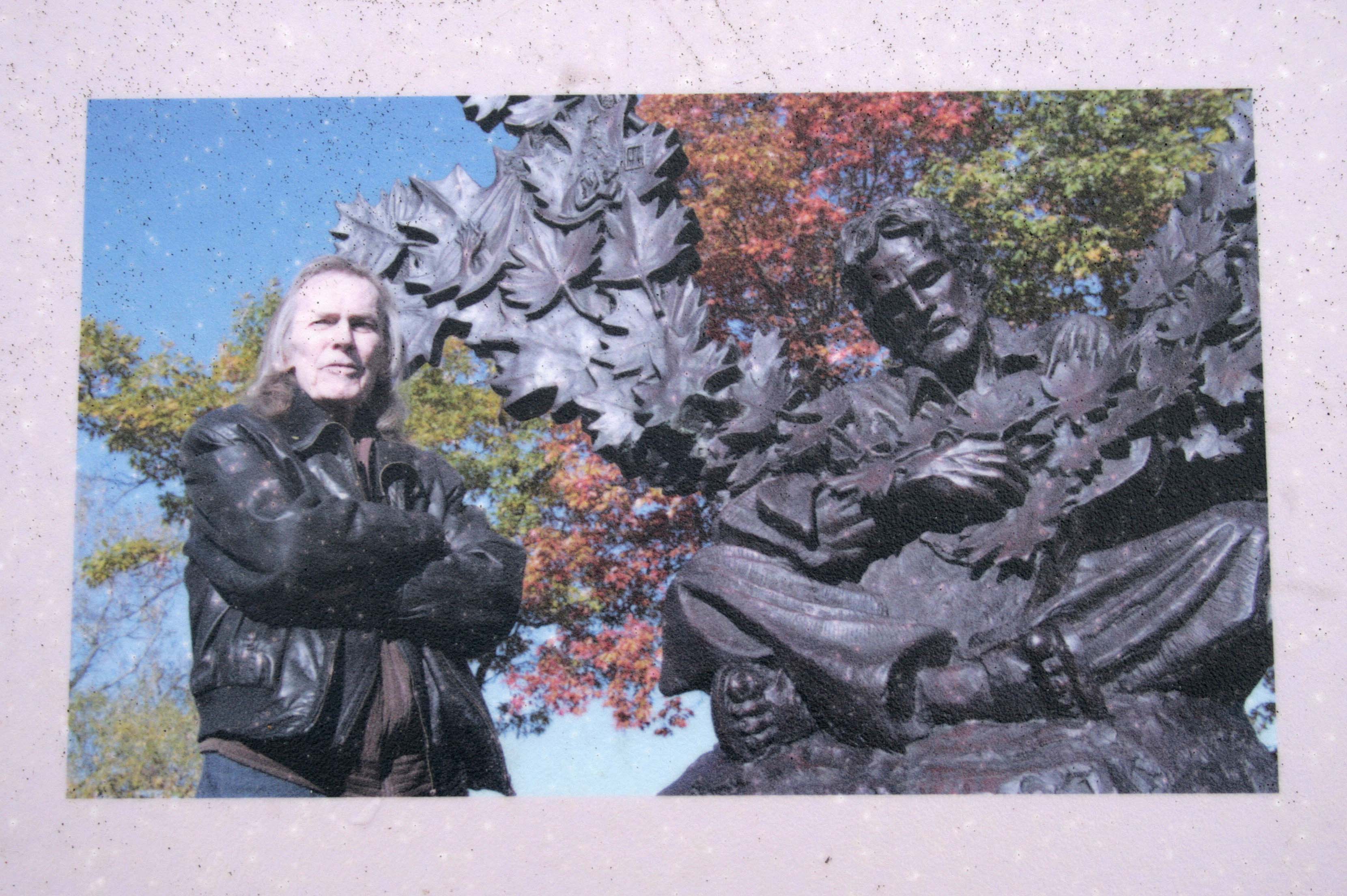

My friends and I visited during one of those truly hot summer days when the heat seems to cling to you, even when you’re standing still. Despite the temperature, the Empire State Building gravestone was impossible to miss. It towers over the surrounding stones, drawing your eye almost immediately as you approach that section of the cemetery.

We were more than happy to slow down and admire it. The monument sits beneath a small grove of trees, and the shade was very welcome after walking through the cemetery in the full sun. We lingered there for a while, taking in the details of the stone and enjoying the brief break from the heat.

John W. Bowser is laid to rest beside his wife, Adaleine McMillan Bowser, who died suddenly in an accident on September 4, 1948.2

Gravesite of John W. Bowser and his wife Adaleine Bowser. Aurora Cemetery, Aurora ON ©2025

Seeing the gravestone brought back memories of my first trip to New York City in 2010, when I saw the real Empire State Building for the first time. Standing at Bowser’s grave, it was hard not to compare the two. One is a towering steel skyscraper in the middle of a busy city, and the other is a quiet stone monument in a small-town cemetery. Even so, both have a presence that makes you stop and look up.

New York City Skyline (The Empire State Building is on the far right), New York NY ©2010

John W. Bowser’s Empire State Building gravestone is a perfect reminder that cemeteries are full of unexpected stories. Sometimes those stories are told through dates and names, and sometimes they rise straight out of the ground in the shape of a skyscraper.

Starting the year with a stone like this feels fitting, and it’s a good reminder to keep looking closely. You never know what kind of story might be waiting in the next cemetery.

Thanks for reading!

References:

- John W. Bowser | Wikipedia

- John W. Bowser, More About an Auroran Linked to the Empire State Building | Living in Aurora Blog

- John W. Bowser’s Empire State Building Grave | Atlas Obscura

- Empire State Building Tombstone In The Aurora Cemetery, John W. Bowser | Living in Aurora Blog

- Empire State Building brought prominence to Bowser | YorkRegion.com