Have you ever heard of best friends being buried together?

That’s exactly what four women in Toronto chose to do. They lived in the same neighbourhood, supported one another, and made sure they’d stay side by side long after their time on earth. Their story is heartwarming, inspiring, and a little unexpected.

In the heart of Toronto’s Prospect Cemetery sits a shared gravestone marked with one simple word: Friends. The four women behind that stone, Pauline Chorna, Annie Hrynchak, Nellie Handiak and Anna Baran, might not be famous, but their story has captured hearts across Canada and beyond.

These women, friends in life and now in death, chose to be buried together as chosen family. Their decision, made decades ago, quietly reflects a lifestyle that’s now becoming more common, one that embraces shared housing and friendship as a way to age with dignity and connection.1

At a time when most people were buried with relatives, choosing to be buried with friends was unusual and incredibly meaningful, which is part of why their gravestone stands out so much today.

“Friends” Prospect Cemetery, Toronto ON ©2025

Thank you for being a Friend

Long before the Golden Girls TV show aired in 1985, these four women had already built full lives rooted in friendship and community. All four were immigrants from the Carpathian Mountains, part of a wave of 20th-century migration driven by difficult economic times2. Some say they may have met on the ship that brought them to Canada.2

They each married and raised families, but no matter where life took them, they stayed close. They met regularly to play cards and catch up at the Carpatho-Russian cultural centre, building a bond that lasted decades and continued beyond their lifetimes.

This kind of friendship, and now living arrangement, is part of a growing movement in Canada known as the Golden Girls model. It’s a new way for seniors to share homes instead of moving into care facilities. It helps fight loneliness and can make housing more affordable. In 2019, a bill called the Golden Girls Act was introduced in Ontario to make shared housing easier and more protected by law.3

The movement has grown beyond Toronto, too. In my hometown of Sudbury, for example, a group of women created the Golden Girls Network to help seniors learn more about shared housing. They want people to know that this way of living can offer friendship, safety, and support. It’s not just about saving money, it’s also about finding joy and community in later life.4

Prospect Cemetery, Toronto ON ©2025

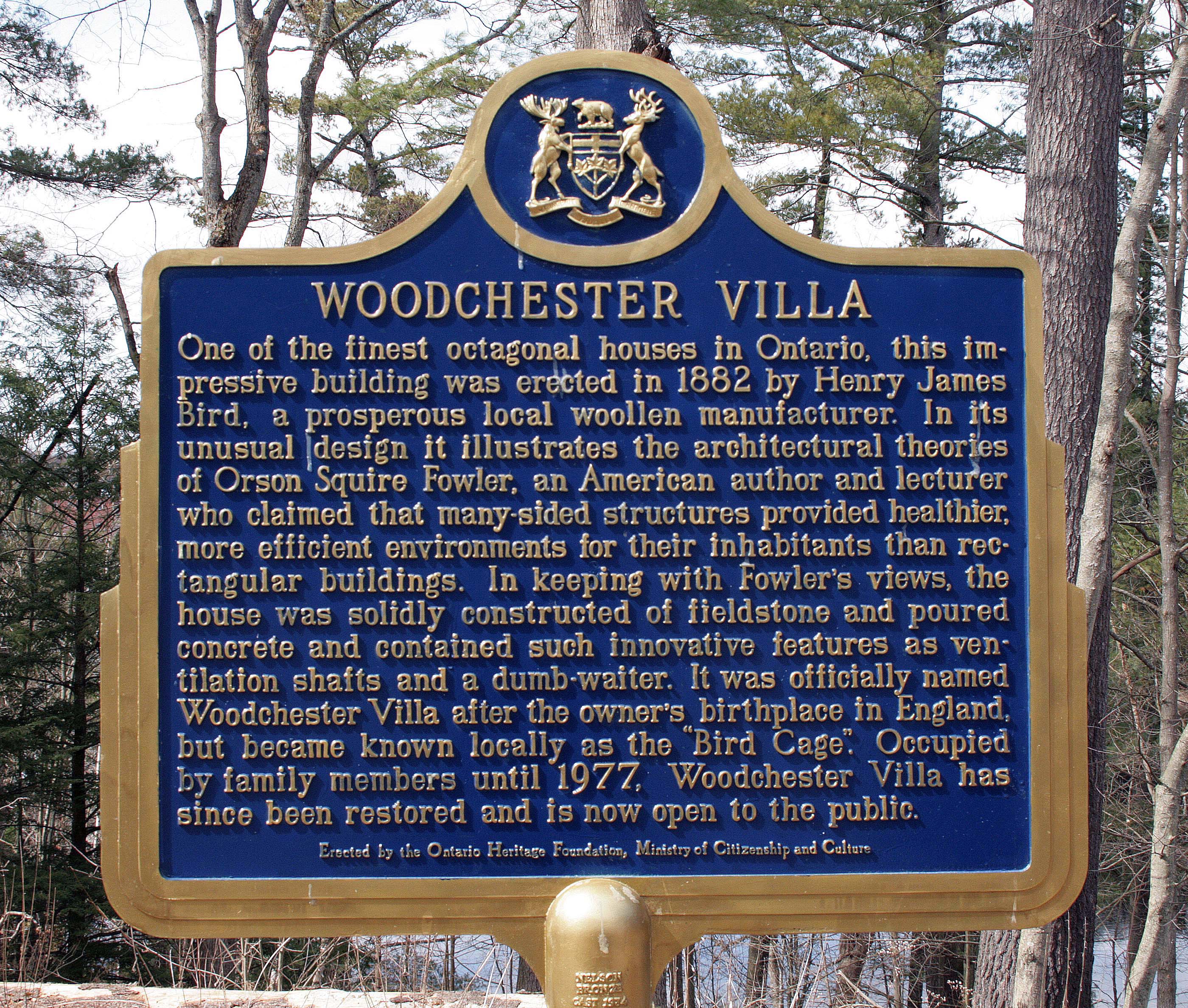

Prospect Cemetery

Prospect Cemetery opened in 1890 and has been part of Toronto’s landscape ever since, with peaceful paths and historic stones that reflect more than a century of stories.5

We visited on a chilly, grey day in late April 2025. My fiancé and I were staying in Toronto with friends, and they suggested we take a stroll through the cemetery. The cemetery is quite large, and many locals use it for dog walks, bike lessons and quiet strolls.

Our friends were more than happy to show us around, especially to show us the grave of the well-known Golden Girls.

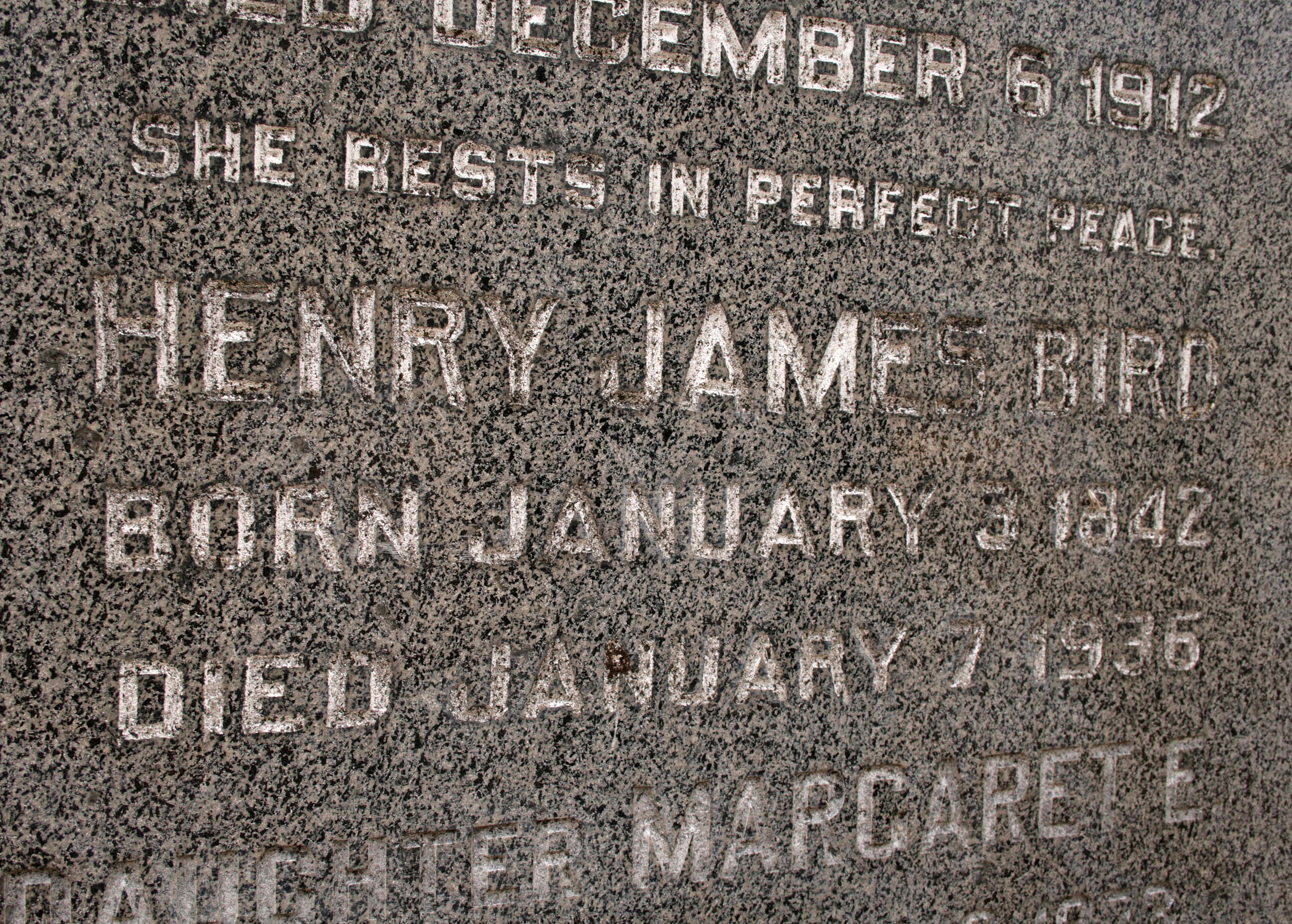

We found their final resting place easily. The red granite stone sits right along the path. At the top, where a family name would usually be, is the word “Friends”, followed by the names and dates for each woman.

Pauline Chorna was the first to pass away on January 30, 1977.

Annie Hrynchak followed on February 6, 1993, at the age of 87.

Anna Baran also passed away on February 6, 1996, 3 years later, at the age of 91.

Nellie Handiak, who had purchased the cemetery plot back in 1968, was the last of the group to pass away.2 She died on June 22, 2006, at the age of 97.

Prospect Cemetery, Toronto ON ©2025

Handiak’s daughter, Jeannie, honoured one of her mother’s final wishes by slipping a deck of cards into her casket.2

When Handiak first told her daughter that everything had already been arranged, even the headstone, Jeannie was taken aback. “Oh, we got that too. We’re gonna be ‘friends’”, her mother had said.2 When asked why, her answer was simple: cards. So when Jeannie placed that deck of cards in the casket, she made sure the four friends could carry on their favourite card games in the afterlife.2

Their story continues to be shared online and in local news, and their gravestone has become a small point of interest for visitors who are moved by their friendship.

So, if you ever find yourself wandering through Prospect Cemetery, take a moment to visit their grave. It might leave you thinking differently about getting older and about how powerful true friendship can be.

Thanks for reading!

References:

- Who are the Golden Girls of Prospect Cemetery and why did they decide to spend eternity together? | Toronto Star

- Best Friends…Forever | Toronto Star (through Pressreader)

- Golden Girls Act to help seniors access shared housing | Registered Nurse Journal

- ‘Golden Girls’ concept expands to Sudbury, Northern Ontario | Sudbury Star

- Prospect Cemetery | Find a Grave